Chapter 2

Effective Ways to Prepare for Afterschool STEM Lessons

Highly effective planning and lesson preparation leads to rigorous, aligned, and active learner learning. To plan effectively, educators need deep knowledge of the end goal for learners and strong daily lesson preparation.

- To understand the end product and key objectives, prepare a learner work exemplar or model in advance. This ensures you have all the learner materials. When possible, it is best to do the activity in the lesson for yourself before doing it with learners.

- Lesson preparation takes the form of deep internalization and customization of provided lesson plans (such as those already written as part of many afterschool STEM programs, such as the A’STEAM from the Children’s Museum Houston).

- This is done through carefully reading the lesson from beginning to end keeping the objective of the lesson central when making decisions for execution of the lesson.

- Additionally, this involves the use of annotations. Annotations involve adding notes to the lesson plan highlighting aspects of the lesson you want to prioritize and emphasize before going live with learners. Avoid reading the scripted talking points so closely during a lesson that you are not focused on learners.

- Effective lessons follow steps that are typically anchored in a protocol or template. Although the order of the steps may vary, most STEM educators follow a similar lesson cycle. The next section details the typical steps in a lesson cycle to provide rigorous, aligned, and active learning in every lesson.

Key points to focus on when you are reviewing a lesson include:

| Lesson Preparation Checklist |

|

Opportunity for Practice: Read this linked A’STEAM lesson plan. Download a copy and practice making annotations for this lesson as if you were going to teach it to learners using the checklist above. When done, compare your lesson preparation and annotations with this exemplar of how an educator marked up the initial lesson plan to effectively prepare for the lesson.

How to Use Media During Afterschool STEM Activities

Using media such as videos and visuals presentations are effective ways to inject visual interest into almost any lesson. When teaching STEM lessons, videos and visuals can be especially useful for making math and science concepts relevant to the real world. Here are some tips of what to do and avoid.

| Do This | Not That |

| Use a consistent and simple design template | Limit flashy special effects |

| Keep some empty space on the slide | Avoid too many words on a slide |

| Minimize the number of words and slides | Limit punctuation and all caps |

| Know how to explain your content without the slides | Avoid reading the slides |

| Keep a power cord for your laptop, speakers and projector ready | Don’t forget to test the audio for videos in advance |

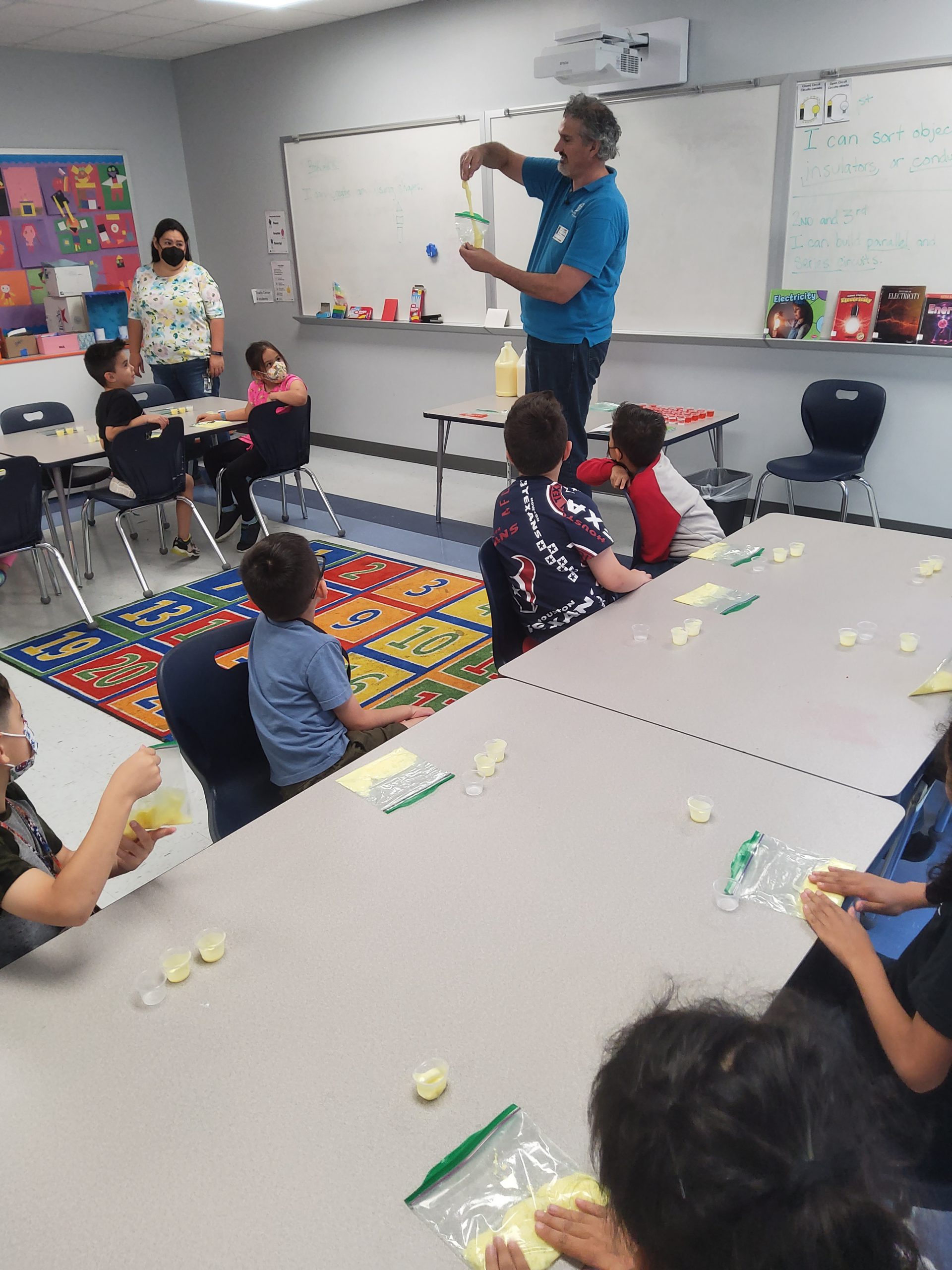

When Should I Give Learners Access to Materials?

When learners have hands-on materials, they are able to actively engage in content. This also builds learner interest and excitement in the lesson.

- As part of lesson preparation and planning, it is important to note all of the materials learners will need during the lesson and to gather them in advance prior to executing the lesson. Consider where to place these materials in your learning environment and to predetermine when to provide learners access to materials during the lesson.

- Typically, hands-on lessons are best executed when learners are grouped together at a table where they are easily able to talk to each other, support each other, and observe what each other is creating. Sometimes learners will need to share materials or co create something together. It recommended creating learner table groups with no more than 4 learners working together at the same table.

- Before delivering the lesson, it is important to make decisions for materials you may want to pre-place on learner tables, so they are ready at the start of the lesson and/or to peak learner interest and motivation. This is also helpful to maximize time during the lesson.

- There will be some materials that you will want to provide to learners during identified times during the lesson. This could be an activity sheet, graphic organizer, manipulatives, and/or supplies. These are materials that you do not want to pre-place in the learning environment, as they could distract learners during the lesson.

- To efficiently provide materials to learners, it is effective to identify material managers in your classroom. A material manager is a predetermined learner who will serve in a leadership role to get necessary materials (when prompted by the educator) for their table group. Assign one material manager per table group. When these materials are needed by learners, you can ask for predetermined material managers to identify themselves and to come forward to get materials for their table group.

- This strategy prevents all learners from moving about to get materials, which is an effective classroom management strategy. This also maximizes instructional time, as you as the educator, do not need to provide materials individually to learners.

Play Video: Setting Up the Environment for Successful STEM Activities

Key Points: Lesson and Materials Preparation

Effective preparation and preplanning will ensure:

- Effective and engaging instruction for all learners

- Educator confidence in delivering instruction and mitigating any challenges

- Carefully crafted visuals and presentations will structure the content of the lesson

Learn More: |

Chapter 1 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | STEM Programs Page |

|---|

References:

Lewis, Beth (2018, June 19). Classroom Jobs for Elementary School Learners. ThoughtCo. www.thoughtco.com/classroom-jobs-for-elementary-school-learners-2081543

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2017, August 8). Tips for Making Effective PowerPoint Presentations. [Legislative staff coordinating committee guidance.]

Smith, M.S., Bill, V., & Hughes, E.K. (2008). Thinking through a lesson: Successfully implementing high level tasks. Mathematics Teaching in Middle School, 14(3), 132-138.